The Dorset Insider, a new sporadic column dedicated to shedding light on local matters with unfiltered honesty and a critical eye. The author – a local parish councillor – will remain anonymous for the sake of candid discourse, but readers can rest assured that their identity is known and trusted by the editorial team. This anonymity allows the columnist to speak openly, challenging the status quo and addressing issues that matter most to our community.

The first the neighbours knew of a planning application next to their home was a notice the day before the consultation deadline. Yes – the day before.

Dorset Council has now devolved responsibility for posting planning notices to the developer, as they no longer have the capacity to place them on sites. It’s quite possible that developers, as busy people, also don’t have time to put sign up – or they simply forgot. That’s only human, we all forget things.

Or maybe it was simply that the wind blew the sign away. These neighbours did eventually find out in the nick of time. But imagine losing the ability to comment on a planning application at all.

Nimby or experience?

Just before Christmas, when people already had their minds focused on the festive season, the Government released two very important papers on devolution and planning.

Launched to a fanfare of “War on the Nimby,” politicians promised that the currently bulging planning bureaucracy would be overcome by making the process easier. Indeed, there have already been incidences where the deputy Prime Minister has waded in to long-standing disputes across the country to sort out the so-called blockages to development.

So what exactly is a Nimby? From reading the new diktat on planning, right now anyone who complains about large developments seems to acquire the title. However, the acronym for Not in My Backyard first appeared in 1979, and was used to describe people who complain about developments or unpleasant projects in their area, such as a new waste incinerator.

The concept dates back a lot earlier, of course: back in 1721 the good people of Smithfield in London objected to the stench of women being burned at the stake (note that the barbaric punishment itself wasn’t the issue) and got the execution site moved to Tyburn.

Who is heard

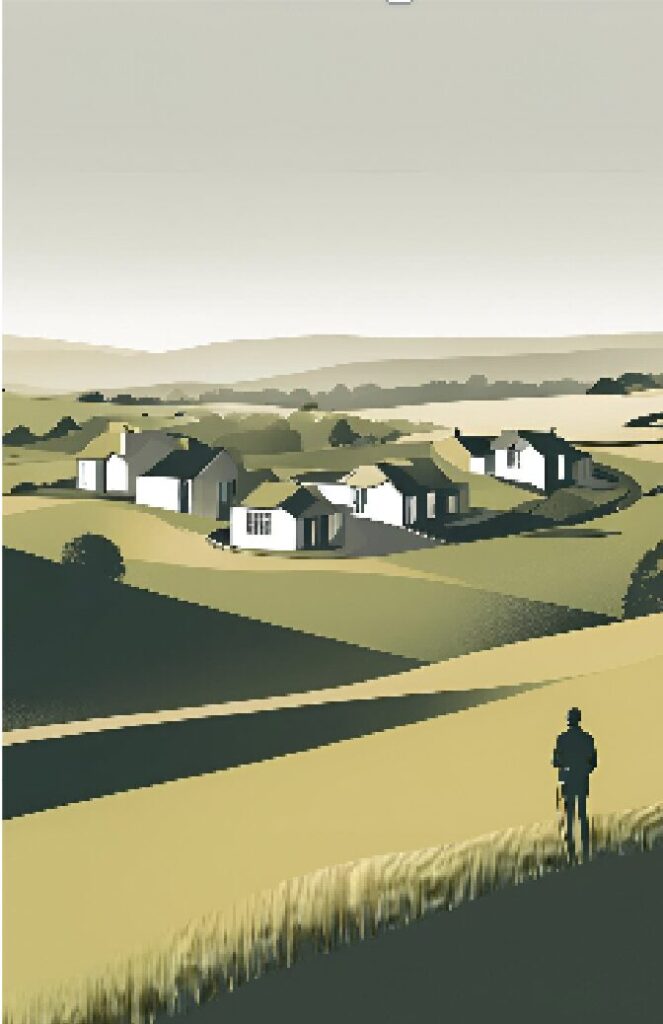

As a councillor, I’m approached all the time by people with concerns about the loss of good agricultural land and the threat of turning villages into featureless commuter transit centres – or, worse still, merging two villages into one as a consequence of the continual creep of new housing onto farmland. While it’s inevitable that every town and village has at least one person who believes everything should remain as it was in the 1950s, the vast majority of those raising issues have constructive feedback and significant, very reasonable concerns.

I’ve learned a great deal from people who have worked the land all their lives – those with deep, practical knowledge of drainage and ditches. What they have to say about the impact of building developments is highly relevant, especially given the rising groundwater on roads in North Dorset.Then there are the growing concerns about road safety, with larger vehicles speeding down narrow roads that lack pavements – basic, valid worries. When local families face the realities of Dorset’s ‘dental desert’ or juggle school runs to three different schools due to limited places, they are rightly questioning the strain on infrastructure. And you only need to visit an A&E department in January to see the effects of failing to expand local infrastructure alongside housing development. These are all urgent, well-founded concerns – yet time and again, they’re kicked into the long grass by successive governments. When planning decisions are made, a very defined process is followed to ensure that the applicant gets a fair hearing and the right to appeal where necessary. So when I see politicians wading into the planning process, or ‘bureaucracy’ being removed, it begs the question who exactly makes the decision on large developments, and on what criteria?

Of course, streamlining the endless red tape is badly needed. But so are the opinions and the engagement of the community around new developments. When we deny the voices of the local people, we are firstly losing out on important perspectives and knowledge, but more importantly, the right to speak freely without being labelled as a stereotype.

A mayor for Wessex?

When the new strategic councils are formed and decisions are taken at a wider regional level, I wonder how any deep understanding of local knowledge can possibly be heard and taken into account. Most of the strategic councils so far have been established in urban areas like London and Manchester. Will a city model work in a rural area? Especially where a mayor is responsible for several counties? And what happens when a difficult decision has to be made, such as one member council being unable (or unwilling) to meet its planning targets? Will the others have to absorb the shortfall?

As strategic councils begin to form, I also wonder about the impact on local council officers, most of whom do a fantastic job in challenging and underfunded circumstances. When I have a parish issue, I always find it refreshing to speak to a Dorset Council officer who knows exactly where I mean in the wilds of North Dorset. But will a super-council offer the same response, or will that local knowledge be lost in corporate detachment?

Most importantly, will we as the people of Dorset, Wiltshire and Somerset get to vote on the proposed mayor, as London currently does, or will these people be appointed through a yet-to-be defined process?